This May Day Let's Discuss the Largest Sector of the Workforce

It's mothers and they're unpaid

With Trump and the right in general bemoaning the declining birth rates in the US there’s one proposal that I actually like among the ideas being discussed: cash bonuses. There is one slight issue with it though: the $5,000 cash “bonus” being proposed is far too low. If politicians want to play a role in helping people with the great expense and hard work of raising children, they ought to pay for the time and effort it takes to do so—and it shouldn’t be called a bonus, rather, call it a wage.

Most recent estimations have found that mothers are working 97 hours per week in the home and if they were paid accordingly it would amount to $115,000 per year (this amount was estimated in 2011) which includes 13.2 hours as a day-care teacher, 3.9 hours as household CEO, 7.6 hours as a psychologist, 14.1 hours as a chef, 15.4 hours as a housekeeper, 6.6 hours doing laundry, 9.5 hours as a PC or Mac operator, 10.7 hours as facilities manager, 7.8 hours as a janitor, and 7.8 hours driving the family car.

Why is all of this labor unpaid? It’s a question some have been asking since the beginning of the industrial revolution, when the work that men, women, and children all did together in the home transitioned to a new economy where men went to work in factories, children went to school, and women were left as the sole caretakers of everything related to the home.

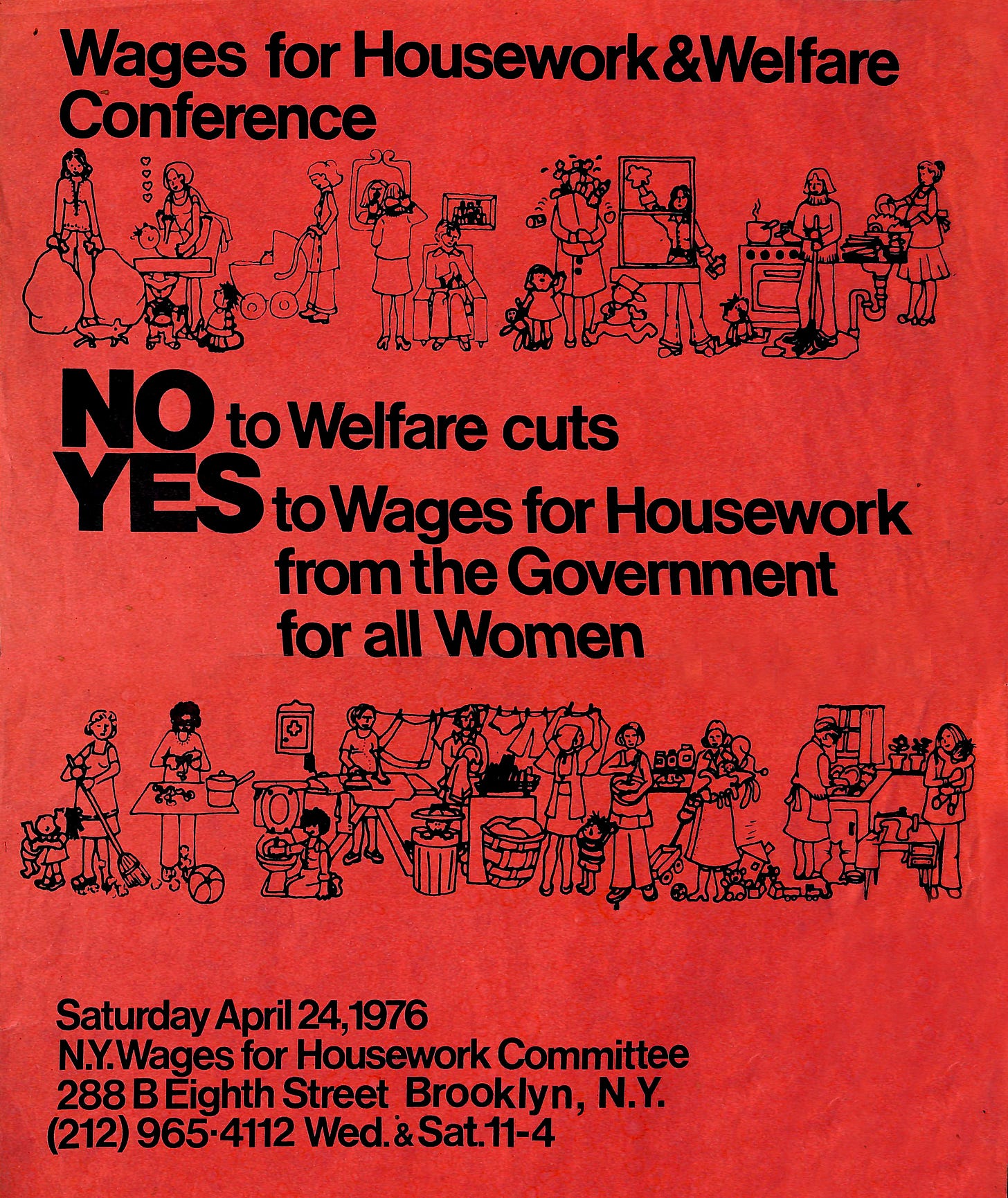

Selma James, cofounder of the Wages for Housework campaign, which arose in the 1970s, argues that once the factory became the center of production, “women, children, and the aged lost the relative power that derived from the family’s dependence on their labor, which had been seen as social and necessary.” Indeed, prior to industrialization the burden of housework fell on the shoulders of everyone in the home: men, women, and children all devoted their energies and time to work in the home and on their land because most Americans were involved in producing at least some of their own food.

Anthropologist Maxine Margolis writes, “Male and female spheres were contiguous and often overlapped, and the demands of the domestic economy ensured neither sex was excluded from productive labor. Fathers, moreover, took an active role in child rearing because they worked near the household.”

Those days are long gone, and in many ways that’s good because much in the era was rife with brutality and oppression; especially toward women, children, anyone not white, and the poor. And yet, we still have such a long way to go toward any semblance of true equality on any of those fronts. I do think though, that James and other organizers agitating for wages for housework are right on track because if you pay mothers directly for their work in the home it cuts across racial, class, social, and cultural divides; it’s uniquely unifying: many of us have to take care of children, we all have to cook food and eat, and we would all like a comfortable place to live.

The emergence of the “trad-wife” is a testament to the fact that there is a yearning—however poorly articulated and lacking historical understanding it is—for something that resembles a time that did indeed value the work done in the home. One (of many) problems with the trad wife motif though is that it’s a performance mostly done on social media with the hopes of monetizing the performance. But what if the actual and real work of caring for children and tending to the home was monetized? No performance or social media audience necessary.

But what if the actual and real work of caring for children and tending to the home was monetized? No performance or social media audience necessary.

I’ve heard those on the right balk at the idea of paying for the care of one’s own family but they readily pay others to do the same exact work: house cleaning services, nannies, day care, schooling, cooking, doing errands, and so on. Meanwhile, left-leaning feminists have criticized the idea of wages for housework on the grounds that it further solidifies a women’s place in the home. Indeed, second-wave feminists prioritized a women’s right to get out of the home and go out to work. Unfortunately that didn’t work out so well for women, who earned significantly less than men in the workforce and were then saddled with the notorious “second-shift” at no pay. These feminists made a tactical error, I think, by emphasizing that the key to liberation was work outside of the home. This prioritized the middle class and in particular white women, because getting white middle class women out of the home often meant that women of color and women of lower economic status were coming into those homes to do the work of cooking, cleaning, and childcare. This is hardly liberation for all women.

Consider this remarkable statement, made by the preeminent economist of the 20th century, John Kenneth Galbraith, in his book, Economics and the Public Purpose: “The conversion of women into a crypto-servant class was an economic accomplishment of the first importance. Menially employed servants were available only to a minority of the pre-industrial population; the servant-wife is available, democratically, to almost the entire present male population.” He goes on to say that if these “servant-wives” were paid, they would be the largest category of the workforce.

I don’t know about you but sometimes I do feel like a “servant-wife” with the amount of cooking, cleaning, and child care I do, mostly by myself, for no wage. I would feel a whole lot better if I were earning $115,000 a year for that work. I still wouldn’t want to do the work in isolation but elevating this work to its rightful paid status would have a significant impact on the culture around “women’s work.” And, just as important, women with that kind of income would then be able to take the time away from work outside of the home to breastfeed their infants, cook healthful foods for their families, and otherwise care for themselves and their families as they see fit. The public health benefits of such a measure are almost inconceivable: ensuring all infants are breastfed for a minimum of six months and ideally much longer, putting money in moms’ pockets to buy healthful foods, allowing the time to actually cook those foods, and alleviating the financial stress that so many mothers face would be nothing short of revolutionary for all aspects of human health.

Galbraith also wrote, “One of the singular achievements of the planning system has been in winning acceptance by women of such a crypto-servant role…And in excluding such labor from economic calculations and burying the separate personality of the woman in the concept of household, where her sacrifice of individual choice would go unnoticed.” [emphasis added]

If Trump et al. want their baby boom they should pay women what they deserve for all their hard work. And more importantly, with or without political involvement, if mothers want what’s best for our families and our larger society let’s reject the role of the servant-wife and interrogate why we accept that so much of our labor remains unpaid.

After the breakdown of my 23-year marriage, I spent my last day before leaving the marital home cooking and cleaning. I felt so guilty about leaving that the least I could do, I thought, was "leave it nice," knowing my STBX had no clue how to cook a decent meal or do even the most basic housework.

As I was mopping the kitchen floor (classic!) I wondered: "Who's going to do this when I'm gone? He'll have to hire someone. Hmm, that'll cost him about $20/hour." And then my math brain kicked in: I added up all the hours I had spent shopping, cooking, cleaning, driving kids around, fixing stuff, taking the cat to the vet, taking kids to the doctor, entertaining them during school vacations (18 weeks a year!!!), and it came to $104,000! After 23 years as a servant-wife, it was only then I realized JUST how badly I had gotten screwed!

Not only do servant-wives not get paid; they also miss out on professional development (I took nearly 15 years out of the workforce to stay home with our kids because my husband traveled every week). Once we got divorced, I had no job to "go back to" as we had moved to the US from Europe 5 years earlier and my European credentials weren't valid in the US, and I was too poor, and working overtime in low-paid jobs, to find a way to improve my qualifications.

Oh -- servant-wives also don't pay into Social Security and don't get credit for the years they spent out of the workforce, raising children; only years of paid work are credited. Sure, I may be able to draw benefits from my ex's Social Security account; long may he live (if he doesn't, that's that).

I'm 59 now and despite a top-notch college degree (that I earned 37 years ago - ha!), several additional qualifications, and having worked hard all my life -- first as a mother & homemaker and then as a self-employed healthcare worker -- I am scraping a living and am not sure I'll ever be able to retire.

Women: think twice about (a) getting married, and (b) staying home to raise your kids in this patriarchal society. Writing this breaks my heart; I adore my children and loved being a mother, but it killed me professionally and financially.

PS: Can you please share a link to the 97-hour study you cite? Thank you.

I think the whole system has to go down...capitalism because even if associating care work with wages can be a necessary and temporary solution for the time being, I strongly believe that any reform that still relies on the tools and paradigms of oppressive systems will keep us stagnating all the while remaining in those same systems existing in different versions only, no radical change. I believe that the definition of work in capitalism is oppressive, tying meaning and importance to monetization aren't a fatality we can create new relatives to escape this hellscale we're in. We can create societies where care work is valuable because it is and because it's valuable for the maintenance of life and culture and every community's member wellbeing as it has been done by many indigenous societies prior to colonisation. I strongly believe it's not with using the tools and structures of capitalism that we will be liberated from it. It sounds very difficult only because we're in a very challenging stage collectively